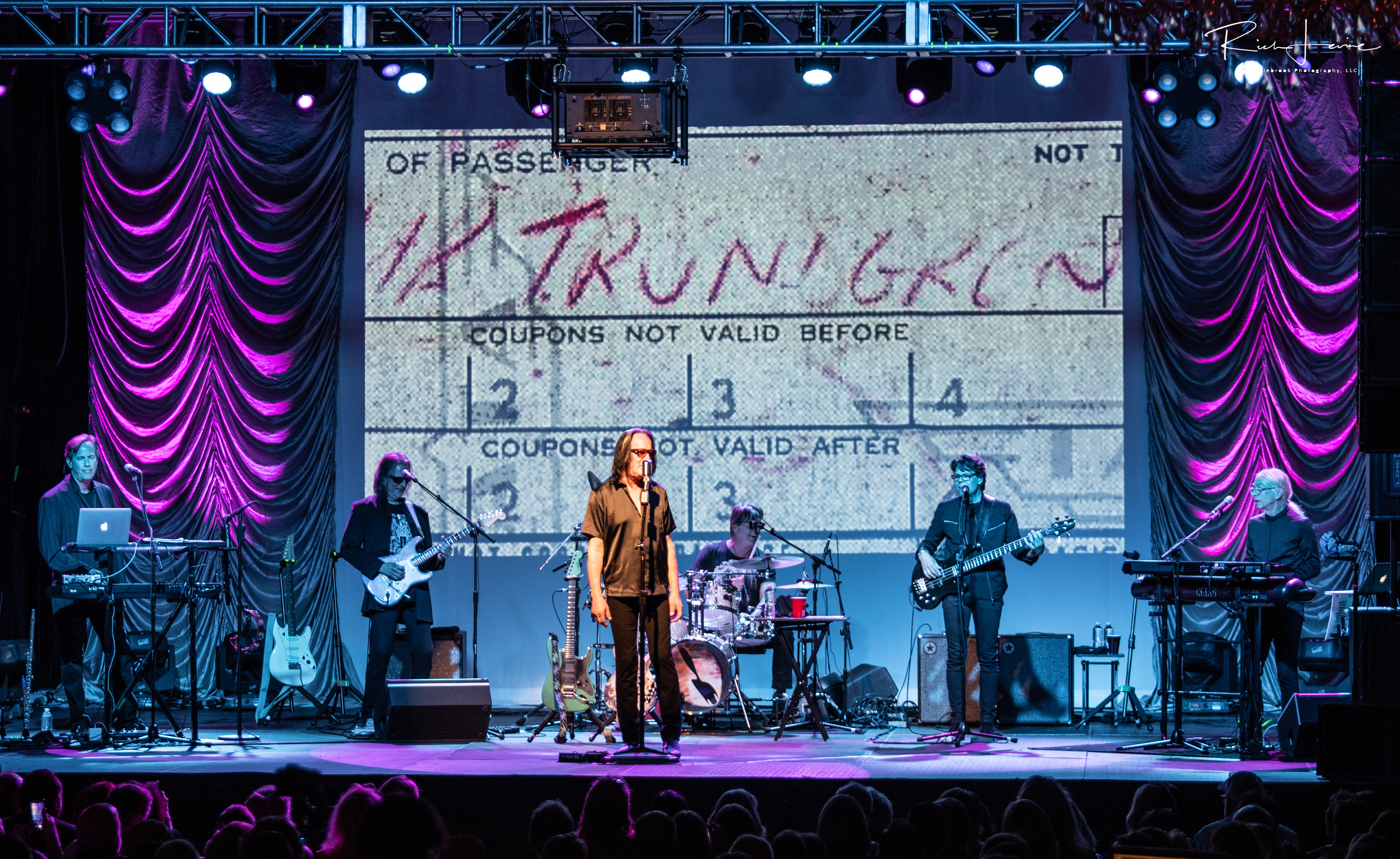

In a strangely suitable coincidence, Todd Rundgren logs onto Zoom somewhere in the oft-titled Music City. After a few days spent off the road recovering from acute laryngitis, the visionary producer and singer-songwriter arrived in Nashville early. Once our interview ends, he'll head over to soundcheck at the Symphony Center to start the home stretch of the "Celebrating David Bowie" tribute tour.

Alongside King Crimson shredder Adrian Belew—The Thin White Duke's one-time guitarist from his Berlin era—the 74-year-old industry veteran has spent the better part of a month leading a band through a highlight reel of his late contemporary's hits. "It's a real audience pleaser, but I needed to stop singing for a while," Rundgren confessed at the start of our conversation. "It's been a grueling tour. We just finished 12 shows in 13 days and that's when I essentially lost it."

For familiar listeners, it goes without saying that Rundgren is no stranger to musical endurance tests, and he hasn't shown signs of stopping. A pioneering one-man production house before the age of the bedroom musician, a loyal adopter of advances in music tech, and a recent 2021 inductee into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, he's continued to carve out an unparalleled niche as one of rock music's most energetic and eclectic polymaths over five tireless decades.

Two years after forming the psychedelic band Nazz, he left the band to lead a double life as a successful solo artist and an in-demand producer-for-hire—a common balancing act in the age of Jack Antonoff and Pharrell Williams, but nearly unheard of in the context of the early 1970's widening sonic landscape. He made records for the likes of Meat Loaf, Hall & Oates, and XTC while simultaneously paving the way for future generations of home studio auteurs through albums like his dizzying 1973 magnum opus of psychedelia, A Wizard, a True Star.

Nearly fifty years on from that record's release, Rundgren's schedule has not slowed down: as the Bowie tour kicked off, he released his latest album Space Force, a twelve-track collection of collaborations that sees the artist take on the task of completing unfinished tracks from musicians of all walks from The Roots to Rivers Cuomo. "Whenever anybody asks," Rundgren says of his work on the album. "I say my role was less of a creative artist and instead wearing my producer's hat." Our conversation began with a walkthrough of that album's making before eventually shifting to a reflection on a life in recording and songcraft.

Let's start with Space Force: Following in the footsteps of your White Knight album, this record consists of collaborations that not only span genres but generations. It sees you reunite with your former studio sparring partners—the Sparks brothers and (Cheap Trick's) Rick Nielsen among them—but you've also invited some younger Gen Z blood into the fold like the Lemon Twigs and Alfie Templeman. To start, talk to me about the process of assembling this cast of all-stars and completing their unfinished tracks. What were you generally looking for out of your collaborators this time?

Well, I wasn't asking them for their castoffs. I was hoping the tracks were something that at least at one point they were very inspired by and or excited to finish. But then it's natural, especially if you're dealing with very creative artists who are coming up with stuff all the time: they’re prolific and almost stumbling over themselves to write songs. They have so many ideas, which is pretty common when you're at the beginning of your career, when you haven't done everything already. The further you get into your career, the more difficult it is not to repeat yourself unless that's your intention. So especially for those younger artists like Alfie and the Twigs, it would probably be fairly easy for them to come up with something.

You go to the other end of the scale with a well-established artist like Thomas Dolby: his song was recorded in the '90s. It wasn't that he maybe never intended to put the song out, but he lost track of all the masters and all he had was an MP3 demo. I had to use all manner of modern technology to essentially deconstruct it and rebuild it again from scratch in order to make a final product out of it, and that also gave me the opportunity to inject myself into it. That was one of the more unusual things, more like an art restoration than me adding anything particularly creative to it.

Sometimes I would get a song from somebody and they wouldn't even have a theme to it. Davey Lane from Australia sent me a song that was essentially just the musical form, but there was nothing but nonsense lyrics and at that point it was totally up to me to figure out what the song was about. At that point, I just kind of closed my eyes, imagined I was hearing lyrics at a certain point in the song, and worked backwards from that.

On White Knight I wrote most of the material—when I wasn’t singing, it was a particular artist that I picked out and said, "Would you sing my song for me?" So this one is a very different record in that regard. It’s not as if I didn't make any creative contributions, but my thought process this time was that I'm the producer of this record and not necessarily the principal artist. In some ways it makes it a more fun record since it never stops in one place—it’s always jumping around different genres, different textures, different voices.

When you were once asked about your work producing for others—I believe this was in the context of your work on XTC’s Skylarking—you described your usual role as a “songcraft agitator”. I love this phrase of yours. Could you elaborate?

When I was early on in my producing career, I would occasionally wind up with a new artist and we would make the assumption that we had everything we needed to make a record. We go into the studio and get three quarters of the way through and then suddenly realize we're short a couple of songs. There’s nothing worse than that: suddenly realizing that you have no song and you have to start from zero and come up with a whole song in the studio. It's very rare anybody comes up with anything great that way. I decided that if you really want to ensure the best quality in terms of the songs on a record, you want to be able to review everything before you do the record.

Oftentimes people have the crux of the idea, but in order to fill out the song form, they write an obligatory bridge—I don't really want to write a bridge, but I have to. It would sometimes become obvious that they didn't really invest a lot in the bridge in the way they did the rest of the song. That’s where the agitation comes in. I'd say, "Go back and try again… Yeah, it's a bridge, it works, words rhyme, stuff like that, but it doesn't add anything to the song. Go back and work on it a little bit more."

And then if we get really desperate and they don't have an idea, I will just step in and start making specific musical suggestions about what they should do. I avoid that because there have been projects in which my participation in the songwriting will leave fingerprints all over the record. For instance, The Tubes' Remote Control, I pretty much wrote all of the song parts on a good percentage of the record. They had all of the musical arrangements already done, but they just didn't know what the song should be about so they never started writing the song itself.

I have a sort of sensibility that I utilize in my own recordings: I always write the instrumental part first before I ever write the lyrics or the melodies. I want, first of all, to have it suggest something to me in the mood of the music—it's still kind of the way that I do things today. Then I ponder on what the song will be about, but I never write any lyrics down until right before I'm about to sing the song. It’s a very strange process. I may spend weeks working on a track and then I will sit down, write the lyrics and sing it in less than an hour. It's almost like I have turned the actual songwriting process over to my subconscious.

The way you talk about process almost sounds like automatic writing.

It's exactly like that. Once I start, it's almost as if my hands have a mind of their own, the lyrics and the melodies just start coming out. I've thought about it so much and my subconscious is much better at this than I am. It loses a certain natural element, a certain natural inspiration—so I keep trying to turn that back into my subconscious. I almost resist trying to write anything down. I will certainly write down snippets of lyrics—“I think that's a great line, I want to use that.” But that's not a song, that's just a line from a song. So, that'll go into my subconscious with everything else and then eventually it does its job. It always seems to come through for me.

I imagine when you're helping others through those motions as opposed to working alone, these tactics are an efficient means of lighting a flame from under the ass.

Yeah, in a way. I think it gets more and more difficult the more songs you write because nobody really wants to repeat themselves unless that's what your music is. Like Credence Clearwater Revival—every song of theirs sounds like every other Credence song. But if you don't want to repeat yourselves, it's challenging. It's hard not to fall back on your habits and your natural proclivities and wind up with something that substantially resembles something you already did.

I find that one thing that helps me avoid that is having some kind of overarching concept for the record. Even though we've gone through a period where albums are not the imminent product anymore. People put out songs all the time and then eventually they'll put out a larger work. I tend not to think that way. I see things as part of a larger phase that I'm going through, a new country that I'm exploring. It’s almost deadly to me the idea that I might repeat myself.

Shifting back to production quickly, though I suppose this applies to songcraft too: as a producer, I often find that there's often this universal line between one's personal perception of a project in the act of production and then how the end product is publicly received. Legend has it that when you made Meat Loaf’s Bat Out of Hell, you were supposedly drawn to the project on the basis of it feeling like a parody of Springsteen, and then upon its warm reception, you couldn't believe the world took it seriously. Talk to me about this relationship between the headspace you're in during the throes of working on a production project and then how the public attitude might shift once it's out in the world.

Well, it isn't just the public attitude. I do admit to being astounded at the reception that it got, but it wasn't the automatic thing that a lot of people assume in retrospect.

It took a lot of work for them to break that record. I gave them the record, but they actually broke it. It wasn't like they released the record and it was a hit. They put out one single, it bombed. Put out another single, it bombed. It wasn't until the third single and a whole combination of other things that may have been just coincidental that caused that record to be such a success in the end—one of which was MTV coming on the air at the time and not having enough videos for them to fill in an entire day's worth of programming. So they would play "Paradise by the Dashboard Light" once an hour. You could turn on the TV any time of day and suddenly there it is—

Wait, the song in its entirety? Did they not edit it down?

No, no—DJs were just like DJs. They wanted to put on The Dark Side of the Moon so they can go up to the roof and get high. (laughter)

Of course.

DJs wanted to find really long so they could goof off for a while, so it was a VJ favorite as well. But once you saw it—the whole spectacle of this giant behemoth and this little girl, the interaction between the two of them—it was so bizarre that you couldn't look away from it. It was like watching a nonstop car wreck in some ways.

That's a perfect description for that music.

They couldn’t stop rubbernecking. Once they did that, they just toured relentlessly and that's how they cemented that whole thing. It was almost backwards the way that it happened. Instead of it coming out and being a big smash and then you released the next single, they had to go back and release the singles that they had released before because nobody was paying attention at the time.

More to your point, it isn't simply the difference between my expectations and audience expectations. A record like Skylarking, it was my expectations and the band's. Before the record ever came out, Andy Partridge went home and to anyone who would listen, he said, "It's the worst record we ever made."

No way.

He said, "It's the worst record we ever made," because that's where his head was at. It was mostly because he and I were at loggerheads. He wanted to hijack the process and I told him at the beginning that I would not allow that to happen because I knew their history. I was a big fan and I loved the records, but I knew what was wrong and I was not going to let them sabotage their career. And even if they hated it, it's like, “Take your medicine!” (laughter)

You fought the good fight, I can tell you that much.

Shifting gears to your solo records: this year and next mark the 50th anniversaries of two of your beloved albums: Something/Anything? this year and A Wizard, a True Star in 2023. On the lion share of this material you were the sole performer. More often than not, when people of my generation talk about your solo work, they often frame it as an influence on the origins of the so-called “bedroom musician”, almost at the risk of a cliché. As someone who went down the one-man DIY multi-track route long before the development of music tech made that a domestic possibility for others, what is your relationship to that phrase?

Well, as you say, we didn't have the technology to allow us to build a studio in the bedroom at that point, although it was very close to that. I'd been working in conventional studios, but especially in terms of making my own records, I had favored the idea of getting a small studio, a little mom-and-pop place you could take over. There was a studio in LA called I.D. Sound, we did both Nazz records there and I did my first three solo records there. In other words, you say, "I want the studio and I don't want anybody else in it."

It was tantamount to having your own studio—that was the way that I wanted things to be. So after Something/Anything? I said, "Going forward, I want my own studio and I don't want it to be like a regular studio." It's a playpen for the little consortium of musicians that helped build the thing and put it together. I bought most of the equipment but it was built in somebody else's space.

I just wanted the whole process to be a little different, to be able to use the studio as a songwriting tool. Previous to that, the expense of being in the studio made that prohibitive for most people. Nowadays, it's fairly common. Bruce Springsteen will go into the studio without a song at all and just stay there for a year until he has an album, they'll do all the writing in the studio. In those days, that was ridiculous. A record label would never put up with that.

It was kind of a new thing to be using the studio as a songwriting tool, to go in and instead of having to memorize the song and be able to play it all in one take, you just punch in a couple of bars and see how it sounds to you. And maybe while you're at it, you add a couple of synthesizer noises to see whether that enhances the atmosphere you're trying to create or something like that. And eventually, I was writing all the material in the studio and essentially it became the inspiration for the material.

Once you understood what you were capable of, what you could do with all the tools there, the tools themselves would inspire you to do weird things like sit there with a bandpass filter, dialing it up and down in time to the music, stuff like that. Essentially changing the sound of the piano or whatever, but in a musical way. That just became the way that I did things and probably the way that I still do things for myself, but I would never do that for somebody else because I wouldn't trust them to be able to come up with a whole album's worth of material if we started with nothing. So if I'm producing somebody, I need to hear all material first just to make sure that we don't wind up in the studio just looking at each other with stupid expression on our faces wondering what we're going to do next.

It's always good to have a blueprint.

Yeah! When I first started out as a producer, I didn't think about all the other aspects that go into it. You have to be a politician and a psychologist. And if you're dealing with a band, there are issues within the band that eventually will arise that have nothing to do with the music, but you're going to have to address them somehow and figure out how to navigate around them. If you don't have music to play, then those are the things that start happening in the music, in the studio. All of the band's other problems are going to be what everybody's talking about instead of, "Should we play an A or an A minor?" That sort of thing. I really need to hear the material just to know that we will be making music when we're in the studio as opposed to dealing with other issues.

The most fascinating aspect of the music you've made by yourself is that you create this illusion of an ensemble pretty effortlessly. I think of a later album like 1981's Healing or a deeper cut like "Influenza", both situations where the individual parts almost feel like performances by players of distinct personalities. In a setting when you're working alone and multi-tracking from the ground up, how much time do you spend developing the sonic vocabulary between instruments?

Well, it goes back to when I first started making records and we didn't have samplers or synthesizers or MIDI or anything like that. Anything you heard on the record, somebody actually had to play. By the time I got to my third record, Something/Anything?, I had been playing a lot of the instruments.

It all goes back in my mind to The Beatles. On the back of Meet the Beatles, there's a picture of the band in their collarless suits in a funny pose, and underneath the picture is a list of every instrument they touched during the course of making the record. I thought, "That's what you're supposed to do. They list maracas, you hired a maraca player." I remember the experience of making the very first Nazz record in LA. I went to Studio Instrument Rentals (SIR) in LA with a yellow pad and walked up and down the aisles and looked at all the instruments. I would say, "Okay, next Wednesday, send those kettle drums to the studio. Okay, next Wednesday, next Saturday, send the vibraphone to the studio. The tubular bells come in on Monday."

"Get me the percussion section of the orchestra's backline!"

Yeah, anything that I thought we could make a sound out of, we'd find things like a thing called a Marxophone—it's kind of like a cross between a zither and a hammered dulcimer, but it's got little springs on it. It's a very familiar sound, from Cream's "Those Were the Days" and a bunch of other records. You press down on a little lever and there's a lead weight on the end of a spring and it vibrates on the string that it hits. So it makes a sound. I had never seen one before, but I said, "I got to use it, I got to write something that uses that or find some place to use it."

As I started taking over more and more of the instrumentation of the records, I started to understand what it is to be a player of those instruments. The next thing after the guitar is the bass for a guitar player, so you have to understand what it's like to be a bass player. What's the difference between a guitar player and a bass player? It's not just a big guitar, it's got a different function. It also has the special relationship to the drums that the other instruments don't necessarily have. That was what I strove to do.

When I learned how to play the drums, I realized you can't program drums in which the drummer suddenly has three arms. A lot of people won't notice that, but subconsciously, something's going on there that doesn't seem right. That takes it into an unnatural realm because suddenly the drummer's hitting more things than he has hands for—

"I've only got two hands!"

You only have two hands so you can't be hitting three drums! (laughs) Even if you're programming the drums, that informs how you should program the drums. Think like a drummer even if you're not actually playing the drums. And so it was that approach to multi instrumentalism that makes what you do even if you're programming it, sound a little bit more natural. And in a way kind of locked in as a group of musicians would be instead of everyone in their own little world, because they're not paying attention to the little details of what makes up a performance.

I want to ask about the skit that opens the second side of Something/Anything? which is a favorite moment of mine in your discography. You break the fourth wall, you introduce listeners to the sounds of the studio and draw attention to all the errors that might pop up in the act of analog recording. What led you to put that on the record? I have to know.

Well, by the time I got to Something/Anything? I started out thinking it would be just a single record, but I hit some sort of songwriting formula at that point. Every day I was cranking out another song and it soon ballooned into an album and a half. My life essentially was recording. I would get up and go to the studio and record until sometime maybe around dinner time, I would go have dinner and then I would go home where I had an eight track machine brought in, and then I would record all night as well. A friend of mine who was a psychiatrist—a high school friend living in San Diego—recommended that I try Ritalin. That was probably a contributing factor. (laughter)

Oh, you can hear it.

Suddenly I could not stop. I could not stop recording everything I could think of. I was doing "Breathless", the funny little instrumental that follows that. I wanted to do a Les Paul thing where you're messing around with the tape speed and that sort of thing, playing things you couldn't possibly play in real time. At a certain point I realized, "I've got an album and a half, how do I finish this off?" That's when I decided I would just do something equally crazy at that point, I would do all live sessions with no overdubs, like when Nazz had to do our demos.

When Nazz was trying to get signed, most labels had studios and they'd give you a half an hour in their studio and say, "You record as much as you can in half an hour." You didn't perfect any one song, you just laid down as many as you could live, and that was the roots of recording. I realized how far I had already come from that, from those basics to now I'm fiddling around with tape speed and making funny jokes about the process and that sort of thing. So I thought it'd be just as unusual for me to do totally live sessions as it was for me to be doing everything all myself.

Would you say that you were hypersensitive to any errors that would pop up—say, hum, tape hiss, or bad editing—upon listening to other people's music? At that point I just imagine you're recording every day…

Well, it wasn't simply that. By the time I got to Something/Anything? I was already a successful engineer and producer. I went through a whole phase where I didn't really want to be a performing artist after I left the Nazz, so I had devoted myself to becoming a recording engineer and understanding all the basics of that, mic placement, where the meters are supposed to be, how equalizers and compressors work and all that other stuff, and producing other people's records.

The engineering was a great advantage because instead of me having to talk to a third party about what we wanted the sound to be like, the man tells me what they want to hear and I make it sound like that. We don't have to kind of figure out another language that an engineer would understand. So on almost all the records that I was producing, I was engineering as well—that interlude was me essentially off with the producer's hat and on with the engineer's hat.

It would be remiss on behalf of Reverb if we let this interview pass without a little bit of gear talk. Let's close with a few rapid fire rounds: What piece of gear would you say has been with you the longest?

The 1176 compressor limiter. If I had no other piece of equipment, that's the piece of equipment that I would want. It was just the most natural sounding compressor and you could make it sound real unnatural if you wanted to, but it was funny how few people actually figured out how to use it in that way—mostly because of the attack and release times and things like that, how sensitive they are and how much they can affect the naturalness or unnaturalness of the final sound. There are all kinds of compressors and people have favorites, but if I had no other piece of equipment, that would be the one that I'd want.

Is there something you sold down the line that you wish you hadn't?

It's funny, I've more or less committed myself to working digitally. I've never bought into the theory that Neil Young could tell the difference between analog and digital, considering he spends so much time in front of a stack of Marshalls making feedback. I think that it's all in the way that you use it and understanding what the limitations of any of it are. But I think maybe the one piece of equipment that I've ever had that I would still like to have was my first synthesizer, which was an EMS VCS3 "Putney" Synthesizer with a Cricklewood keyboard.

Is there something you used on this new album that you haven't before?

Let me ponder… As I mentioned with the Thomas Dolby song, that was recorded in the 90s and he had lost all of the masters in the ensuing time and that's the reason why he had never released it—all he had was an MP3 demo. I used some fairly sophisticated separation technology in order to break it down into at least five components before rebuilding it again and shadowing a lot of the instruments with new instruments in order to give them clarity and space that had been lost in the MP3 mix. The MP3 might have been just a rough mix so the voice was not loud enough.

I don't nominally do that. The only time I've really used that sort of technology is if I wanted to create a karaoke track, to remove the voice or something like that. But I had never done anything so comprehensive as to try and completely deconstruct what essentially was a fairly low-bitrate piece of music and turned it back into something that sounded like a full spectrum multi-track master. I hope I don't have to do that much again, but it does kind of point to other possibilities of what you could do with old records.