The outsider artist from West Virginia's Coal Valley region Hasil Adkins is an example of ingenuity out of necessity. Born during the Depression, Adkins grew up poor, reportedly remaining shoeless until he was five years old. He wouldn't have a proper studio recording session until 1987 for his album The Wild Man. But thanks to the band The Cramps and Norton Records, who first approached Adkins to release his early music, we have a hazy picture of the beginnings of psychobilly as a genre: lots of tape hiss, whistling, foot-stomping accompaniment, and crudely mic'd vocals from his makeshift recording shack. His engineering was as intriguing as he was. What he lacked in resources, he made up in conviction.

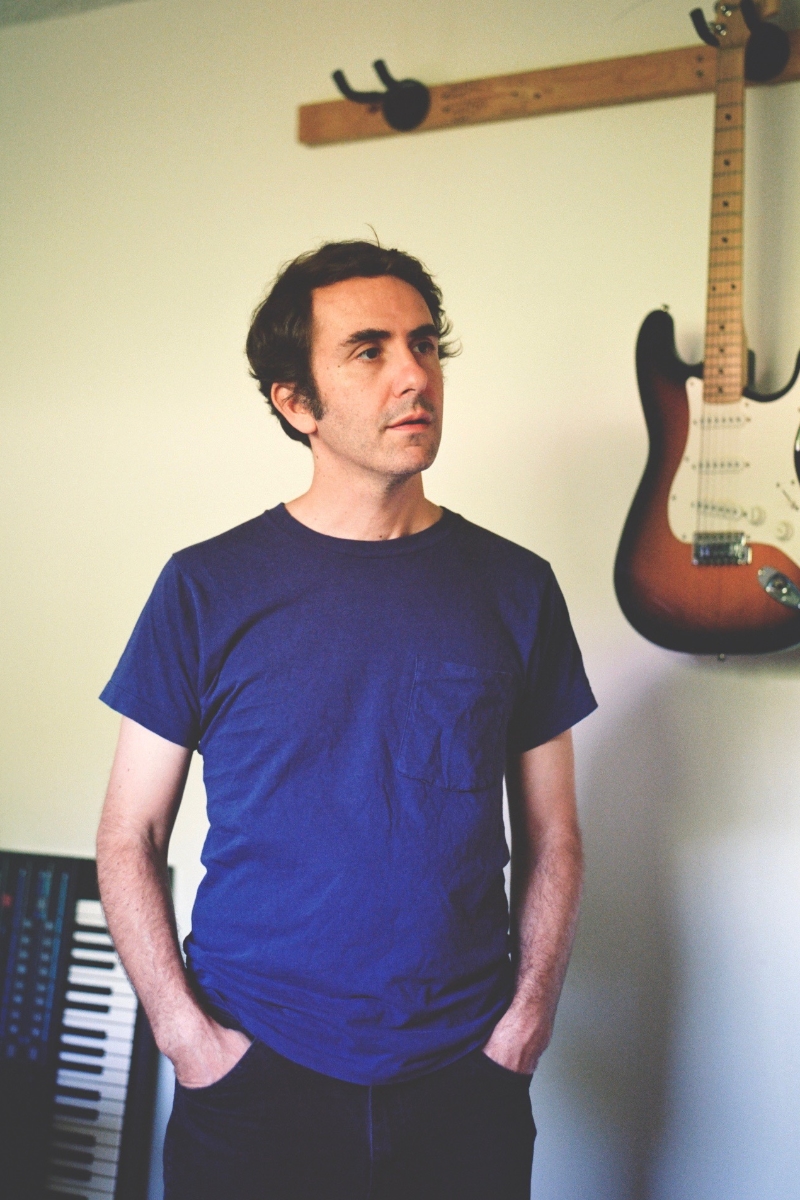

Chris Cohen, a fan of Hasil Adkins, is another in a long line of stalwart home recordists—those who eschew the elaborate, expensive studios, with XLR cable noodle salad at their feet, pop filters made of stockings, and the gift of Gaffers tape.

Cohen—a solo artist, producer, and former guitarist for Deerhoof from the Apple O' through The Runners Four—co-produced Weyes Blood's Front Row Seat to the Earth in 2016, as well as Jared Leibowich's Welcome Late Bloomers, EZTV's High in Place, Itasca's Spring, and a host of upcoming projects from Charlie Hilton, Rodrigo Amarante, Ohmme, Camila Webb, Marta Solbakken, and other artists. When not working elsewhere, he's almost constantly recording in his modest home studio.

In a previous interview I had with Cohen, we touched on the understated complexity of his last record [the self-titled Chris Cohen] but also his past projects like 2012's Overgrown Path and 2016's As If Apart. When asked if he felt his "voice" is best heard through singing, playing an instrument, or in engineering he said:

"I think it's best heard singing or playing instruments. It's there when I'm engineering my records, but when I'm working for someone else there's a lot that is already given. You're really trying to give the artist what they want. Every relationship is different, of course. There are those gigs when the ideas are mostly coming from me but that's rare. I try to intuit what the artist wants. When the record is done, I really want them to be happy. I'll be happy too but it's their dream not mine. I give my two cents when asked and I can be opinionated if that's helpful but I'd never force my vision or make an artist compromise theirs. It's a nice exercise for me to get inside someone else's head for a while and I always learn something."

Below, we get an inside look at his studio, his practical approach to home recording, and a specific technique he uses to record his bass guitar.

To learn more about Chris Cohen and hear his music, click here.

Favorite records to come out of home studios?

All of the Hasil Adkins material, The Residents Meet the Residents, Blanche Blanche Blanche Open Session Rock, The Lentils My Pillow Lava Part Zero: Zero's Revenge, Laraaji Vision Songs Vol. 1, Royal Trux s/t (1988), Mediko Doktor Vibes Liter Thru Dorker Vibes, Ariel Pink House Arrest, Dwarr Animals, The Homosexuals Record The Homosexuals' Record, Jem Targal Luckey Guy, Raymond Scott Manhattan Research, or Deerhoof Half-Bird.

I picked Les Paul's The New Sound record because it's recorded in a home studio that was actually more advanced than an average commercial studio of the time. His was one of the earliest studios to do overdubbing. It's also on a major label and not marketed differently than any other record, so it confuses modern distinctions about DIY or home recording. It's also super beautiful and has a particular quality that would be impossible to emulate.

What makes a great session?

People's spirit. How they approach the place and each other—their attitude towards time and recording. Usually, I can tell if it was great when I hear it back the next day. I can't always tell at the time. For me, the best is when people have a regular thing they do whether it's a performance or recording strategy that they've developed, then the recording process is built upon that.

"Studio B" is what we decided to call Chris' home studio. "Studio A" is a shared space in Los Angeles that he also occasionally works out of. You've heard (or soon will in Amarante's case) some of its output on records by Rodrigo Amarante, Weyes Blood, and Itasca.

We could have done mic'ing tutorial with his Gibson SG, however, it was stolen from his van at a gas station in Los Angeles last summer. Chris instead shared a short recording of his fretless, semi-hollow Hohner with its woody texture and double bass quality. "I used this bass on my new record," he interjected.

The bass was run through a Princeton Reverb amp and recorded with a Shure SM-7B before meeting an Apollo Twin audio interface. He also went on to explain a mic'ing technique that no one but me is calling the "secret sauce." This technique requires an extra microphone placed off to the side and mixed without much high frequency.

"A Rode NT3 was the only microphone I had for awhile. I think the key is to have used something many times. It is not how good the thing is or your skill necessarily but being comfortable with it," Cohen says. "Even if I go to a fancy studio and they have things I've never used before, I usually try to stick to the things I know. Partly, to not waste a client's time but also because they like the sounds I've already gotten. I stick with those."

This hot mic gives a live feel and spaciousness when panned slightly. Cohen explains:

"I started doing this because when I was doing overdubs I would leave the drum mics on. So, now I always leave a microphone in a corner while I do overdubs. I'll have one mic close to the amp—the louder it is the better for the room mic. I EQ the high-end out of the room mic and compress it so you hear things happening at different times and get a stereo effect texturally. I like to mix it to the side. Just using a little bit of it makes a track sound roomier or further away. I usually have it set for the entire track but you could add or take it away to change perspective."

To round out the whole process, "I mix everything down to four stereo buses and I run it into a Sony MX20 Mixer so instead of bouncing in the computer I put it through the mixer and I record it as a stereo file—and that's the finished music. I think this would be the case with other mixers too, but I like this particular one because I think it cuts off some really low and high frequencies. It does some dynamically subtle things. The difference is subtle but I can hear it on headphones."

What are some records that encapsulate their moment in time?

That's tough. Some seem to do that more than others but, ultimately, I don't believe in records encapsulating moments. The "moment" is in the mind of the listener and we are manufacturing that. Our success in creating that illusion is what makes a record great or not. Many times that illusion isn't created and the record has failed. The greatest records do what you're talking about—they seem like a window or portal that takes you to a place that feels real. Putting all the different sounds together is the work. It doesn't happen automatically.

Recording engineers you admire or enjoy?

Betty Cantor (Grateful Dead), Sylvia Robinson (Sugar Hill Records), Delia Derbyshire (BBC Radio Workshop, Doctor Who), Laurie Spiegel, Joe Meek, Spot, manager Kit Lambert (The Who), producer Eddie Kramer, John Dieterich & Greg Saunier (Deerhoof), and Cate Le Bon.

I was just working with Cate on a session and she was so inspiring. She comes up with amazing parts and hears things in a really musical way. As a producer, her feedback is concise and friendly but demanding. She didn't give up on things too quickly when there was something to be gained but also knew when it was time to move on.

What's an engineer-musician pairing you'd like to highlight?

I'm a big believer in artists being their own producers. I'm not totally sure the two are different, but here's an example of how a producer and artist collaborated and made something that I consider important.

Meat Puppets (1982) was produced by Spot. As Spot tells it (I asked him once in a Q&A), the band felt uncomfortable when they first set up in the studio. What they ended up doing to remedy the situation was they turned their amps around and pushed them right up against the drums. For some reason, that made things better for them (they were high on mushrooms).

Anyway, Spot's first reaction was that it was a bad idea. The drum mics would be completely overtaken by the guitar and bass and there would be no separation. But he acquiesced and in the end, this is what makes this album sound really insane and special. It relates to your question about moments. Spot and the Meat Puppets manufactured this sense that we now have of it as a time capsule by means of forced perspective. The record couldn't be mixed in a normal way due to all the bleed.

It gives you a strong impression of that time and the circumstances more so than if they had done it in a "reasonable" way. The illusion that we need to create a moment is manifested by adapting and trying something different, by being open to the unusual demands of each situation, and also people being respectful of each other.

Do you have principles regarding making suggestions or being creative with recording techniques, etc.?

My ethos is to approach music and artists on their own terms—see what they need from me, see what I think I have to offer, find a harmonious way to work. A lot of recording is just being there to support and have a cool head and keep the machine rolling so they don't have to worry about technical stuff.

As an engineer, what do you believe your role in the final listening experience is?

It's a gray area. Many engineering decisions are musical. To me it's mostly about judging apparent loudness and EQ and seeing what the artist wants the listener to pay attention to most. Your job as an engineer is to prioritize those things. For me, a lot of mixing and recording comes first from the artist, their compositions and arrangements, and the timbre of the instruments. In an ideal world all the sounds and arrangement are perfect coming straight out of the band and I just have to stick a mic in front of them.

Do you think engineering is an art or a science?

Definitely both!