Sometimes when you buy a guitar, you get more than you bargained for. In Lynn Wheelwright’s case, he was pretty sure he was getting more—but then it got tricky.

Lynn is a well-known collector and diligent researcher, and his knowledge and perseverance paid off back in the early 2000s when he noticed a blond Gibson ES-250 for sale in a Vintage Guitar magazine ad. As part of his deep dive into the history of early electric guitars, he’s always on the lookout for items from the dustier corners of electric archaeology. And an ES-250 is a rare bird at the best of times.

Launched in 1939, the 250 was among the Gibson brand’s earliest electrics and the company’s first high-end professional electric Spanish guitar. It marked a distinct upgrade from the groundbreaking ES-150, with a wider body, carved spruce top, two-piece maple neck, and the pickup’s bar polepiece now cut into six pieces, intended to sense each string individually without crossover.

The 250 lasted just 13 months in the Gibson line and seems to have been built as more or less a custom model, given the number of variations during its short lifespan. It didn’t take Lynn long to decide to call the seller and find out more details for his growing database. After a few moments of uncertainty with a flashlight and a hard-to-read serial number on the guitar’s label, the owner declared it was definitely 96030.

Lynn had to hand the data he’d compiled during a visit to Gibson HQ and its early records when he was researching another ES-250. Now, though, he searched for 96030. And there it was: April 19, 1940, 1 ES-250 (Sn 96030) sent to Chas Christian, along with a 600 SW case and an EH 150 amp (Sn 12706). Chas Christian? That must be Charlie Christian, the brilliant pioneer of early electric jazz guitar! Whereupon Lynn sat down, weak at the knees. He managed to ask the seller to check one more time. Yes: definitely serial 96030.

Lynn struck a deal and bought the guitar. A few days later, FedEx unloaded it at his door. "I’ve opened many a guitar box in my life," he admits, "but this one had my hands a little unsteady. I took the tweed case into the house, sat it on the kitchen counter, and stared at it. I thought about how Charlie might have carried it with him to those smoky all-night jams. And I was reminded of a story Les Paul would tell about how he would cruise Harlem, looking for guitarists to put in their place. Which he did—until the night he ran into Charlie."

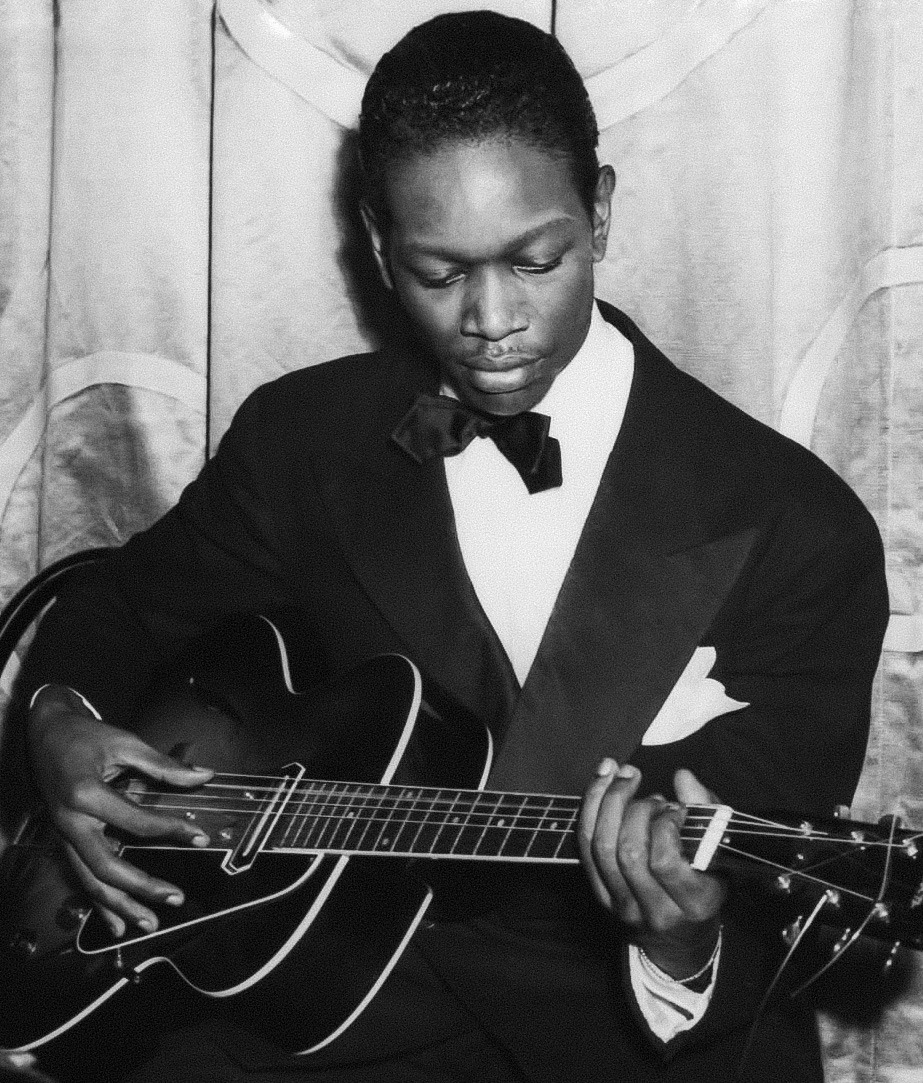

Charlie Christian was, as Les discovered, a mighty player. And arguably the most important musician in the early history of the electric guitar. He had just turned 23 years old in August 1939 when he joined jazz bandleader Benny Goodman’s ensemble, and he became famous in Benny’s band, where he used several Gibson guitars.

Tragically, less than two years later, he died after contracting tuberculosis, but in his short professional life Charlie demonstrated in magnificent fashion how the electric guitar could work as a soloing instrument in jazz—and, by implication, in other music, too. He remains the first hero of the electric guitar.

Meanwhile, back in Lynn Wheelwright’s kitchen, the newly arrived ES-250 began to reveal some secrets. Lynn noticed the way the Gibson logo touched the top two tuner bushings, a detail he’d only ever seen in period photos of Charlie and an ES-250.

He saw, too, that the guitar had been refinished, and the back and sides of the headstock were painted black. The figured back of the body caught his eye, and it was two-piece, which was unusual. He looked through the treble f-hole to see if the grain pattern on the back matched inside to out—it did—and in the process noticed Gibson’s Factory Order Number (an "FON") stamped into the back, reading 7595 H 13.

Gibson used FONs to track production batches through the factory. In the late ‘30s into the early ‘40s, the letter in an FON indicated the year of manufacture, from A for 1935 through H for 1942 (with some overlaps into the following year). And that, to put it mildly, gave Lynn a shock. According to its serial number, this was the guitar shipped to Charlie in April 1940. But here’s an unquestionably genuine FON for 1942. Now what?

Panicking just a little, Lynn tried to calm himself by once again consulting his data from Gibson’s pre-war ledgers. Not that this was an easy task. The surviving books—the ones Lynn consulted at Gibson for his earlier research—are pretty chaotic. There are roughly 163,000 handwritten entries in 3,500 pages of jumbled history, in no rational order, starting in March 1936 and ending in May 1944.

Anyway, he dove in, first of all double-checking the original entry for this 250’s serial number in 1940: it was exactly as he’d seen it. And then he spotted the guitar again, listed for April 8, 1941: one ES-250, Sn 96030, shipped to N.Y. Band. These details had been written into Gibson’s ledger in red ink, which Lynn knew meant a guitar returned to the factory for repair and now being shipped back to where it had come from.

"So Charlie’s guitar had apparently suffered a misfortune," he says, "had been returned to the factory, then repaired, and then shipped back to New York Band, a large wholesale and retail company that also served as Gibson’s East Coast warehouse and showroom. Visiting musicians were solicited to try the company’s latest offerings there, and Gibson could take advantage of a photo op. But now I was wondering when this guitar was shipped back to Gibson, and why."

He turned to two sources for more clues: the soloflight.cc website for its gallery of dated photos of Charlie in action, and Peter Broadbent’s book Charlie Christian: Solo Flight—The Seminal Electric Guitarist.

They confirmed that Charlie had several Gibson guitars in his short career, including ES-150s and ES-250s. Of the 250s, there was a promo-photo-only sunburst model with stair-step headstock, and a few blond versions—mainly the one Lynn had found, which was characterized by "open-book" inlays and its heavy split-Y tailpiece. But also Lynn surmised that Charlie acquired or borrowed a further blond 250, with "windowpane" inlays and a bar tailpiece, while the other was being repaired by Gibson.

With this in mind, Lynn took a closer look at his 250. He spotted a splinted repair of the top center-seam, hidden by the tailpiece, another from the tone knob back to the binding, and a small split near the treble f-hole, all covered by the old refinish.

However, there was still the unusual two-piece back and a 1942 FON on a guitar that Charlie was supposed to have used in 1940 and ’41. Digging deeper into Gibson’s records, he deduced that the FON dated the fitting of this "new" back to some time around November 1942, eight months after Charlie’s death. "As to what became of this 250 after the repair," Lynn adds with a shrug, "well, it could have been taken home by an employee, maybe, or sold out of the factory. It’s anybody’s guess."

He still needed something to irrefutably connect the guitar to Charlie. Then he recalled something he’d heard from Peter Blecha, who had been the curator at Paul Allen’s Experience Music Project in Seattle. Peter told Lynn how he’d verified the Stratocaster that EMP bought as Jimi Hendrix’s Woodstock guitar by photographing quality close-ups of the neck and matching its figured maple patterns to video stills of Jimi playing at the festival. Lynn decided to try a similar technique.

He scanned a photo of Charlie playing the ES-250 that showed in good detail the figured maple on its lower side. Lynn then took shots of his guitar, trying to match the lighting and angle. "From a fixed point where the pickguard bracket attaches to the side, I marked the top of each grain line with a number corresponding to the same numbered grain line I’d marked in the 1940 picture. I got to eight and had gone only six inches up from the bracket, and I could see at least five more in the next few inches—but by then I was convinced. I had the proof I’d been seeking."

In the years since then, Lynn has made sure his Charlie Christian ES-250 has got out and about. It’s been exhibited at museums in Carlsbad, Oklahoma, Scottsdale, and more, and it’s been played by Pat Metheny, Brian Setzer, George Benson, and others. "A lot of guys collect stuff, stick it in a vault, and that’s the end of it," he says. "I believe it’s important to make opportunities to get important guitars like this seen publicly and played by people who know how to play them."

Julian Lage certainly knows how. He played it at the Musical Instrument Museum in Phoenix last September, and there’s a great YouTube clip of him performing there, easing into the Charlie-inspired ‘Seven Come Eleven.’ "This has to be the coolest guitar ever," Julian commented, "completely modern and historical at the same time."

One of several coincidences that marked Lynn’s discovery of the ES-250 was the fact that Charlie’s name was in Gibson’s ledger at all. "This is unusual," Lynn confirms. "Very few instruments bear the name of the recipient in those logs. Had he not been in California with Benny at the time but in New York, he would most likely have just picked a guitar from existing N.Y. Band inventory, and the serial number would have remained a mystery. So here was a very rare model, anyway—but also I’d found the guitar that one of the most influential guitarists who ever lived had used to change one of the most popular American music forms."

There was an uncanny dimension, too. "It was almost cosmic," Lynn says with a smile. "Turned out I bought this guitar on the same day of the month and the same day of the week that it was sent to Charlie back in 1940. I realized this afterwards, that I had bought the guitar on the exact same day of April and the same day of the week, Friday, that it was shipped to Charlie—only 62 years later. I mean: Are you kidding me?"

Maybe this historic Gibson qualifies as one of the last great celebrity-owned guitars to be unearthed—in Lynn’s view it’s right up there with that ex-Jimi Woodstock Strat. But he reckons there could still be undiscovered gems out there somewhere. "You just have to diligently pay attention," Lynn says. "You’ve got to know what it is you’re looking for, and you have to put in the time and effort to figure out what’s what. To be honest, you do need back-pocket information. But as I found out, you just never know when something might pop up."

About the author: Tony Bacon writes about musical instruments, musicians, and music. His books include Legendary Guitars and Electric Guitars: Design & Invention. Tony lives in Bristol, England. More info at tonybacon.co.uk.