Jump in your time machine, set the dial to Britain at the point when the late ‘60s morphed into the ‘70s, and catch performances from some of the era’s seminal bands: the Stones, Led Zeppelin, The Who, Fleetwood Mac, Jethro Tull, Pink Floyd. You might see them at local gigs or at the birth of the UK’s open-air festival movement—in 1969 with the Stones in Hyde Park, or at the Isle of Wight festivals of 1968–'70. One thing they all shared was a reliance on pioneering PA equipment created by a single company, WEM. It stood for Watkins Electric Music, and it was the brainchild of Charlie Watkins, a most unlikely innovator and audio pioneer.

It wasn’t just British bands who liked the sound and the features of WEM PA. American artists visiting the UK also took a liking to Charlie’s gear, notably The Byrds—who played an important role in the WEM story—and Janis Joplin, who took Charlie on tour with her in the USA to oversee her own WEM PA system.

Prior to the birth of WEM PA, live gigs in the UK and Europe had suffered from truly dire sound. Most touring artists had to rely on house systems that hadn’t been improved since the ‘40s. When artists wanted something better, all that was on offer were mixer amps—rarely offering more than 100 watts output—driving pairs of 4x10 or 4x12 column speakers that stood at either side of the stage.

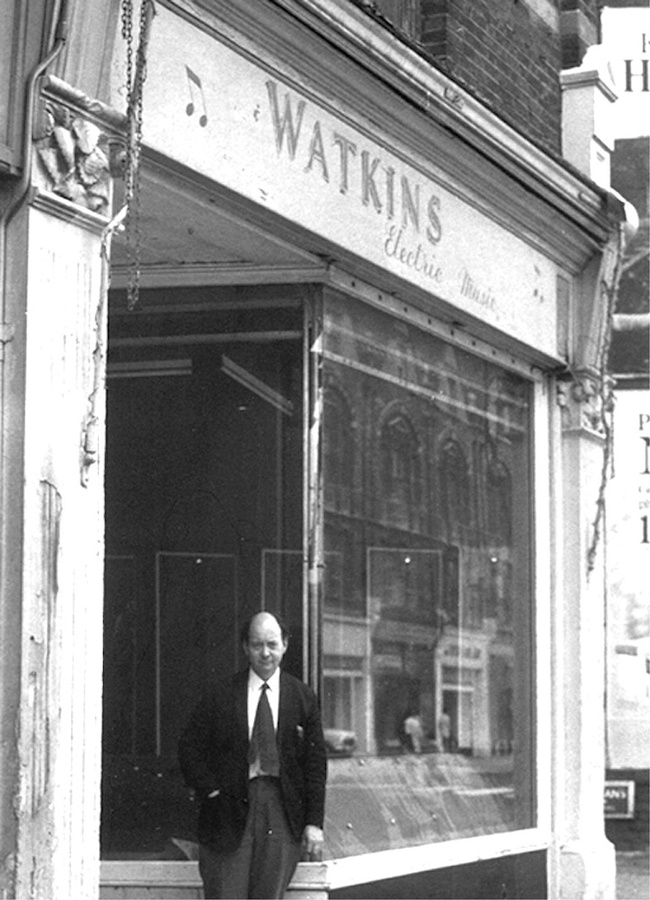

Charlie Watkins, who died in 2014, changed all that. He was born in 1923, and by the ‘60s he was already a successful manufacturer of amplifiers, having launched in 1954 his Watkins Westminster guitar combo, followed later by the more ambitious Dominator and then the Copicat tape echo, which was to become a legend in its own right. But PA, he told me when I interviewed him in 2010, was an entirely new venture.

"I think it began one night when I went to see Johnny Kidd & The Pirates," Charlie recalled. "That started me going out to see what was being played, rather than just sitting in the office. And wherever I went, you couldn’t hear the singer. There was nothing but this dreadful PA at the time—no foldback monitors, just a guy with a Shure Unidyne or an old Reslo ribbon mic and a hopeless PA system." Charlie said he got his biggest laugh from the house PAs that artists often had to use. "They had these line-source systems, and they were terrible! It was usually horrible old war-surplus equipment with 12-inch hard-cone speakers in boxes spread all round the hall. I don’t know why it went on so long."

He remembered The Byrds coming to Britain in 1965. "They didn’t want the sort of rotten PA everyone was using. I don’t know what they’d been using in America, but it was probably as bad as it was here, and they didn’t want to bring W-bins [folded-horn cabinets originally designed in the ‘30s for cinema use] with them. So their tour promoter called me and said, ‘For £100, I’ll let you build a PA for The Byrds.’ It seemed like a good idea to me at the time—I could do with getting into the PA market."

Charlie’s first attempt was, he admitted, pretty awful. The band’s first gig was in Nelson, Lancashire, but Charlie couldn’t make that. "But the next morning—well, if there had been a big hole, I’d have crawled into it! David Crosby was on the phone saying, ‘Expletive-deleted rubbish!’ So I went out with them the next night to see what was wrong, and the moment they started up ‘Mr. Tambourine Man’ it was obvious they were right. You couldn’t hear a word."

Rather than give up, Watkins was inspired by the challenge. "I thought to myself, well, this PA thing is harder than it seems, but I want to do it even more now after all that trouble." Impressed by his willingness to work on the problem, The Byrds on a return visit in 1970 turned to WEM again and bought a system to take home with them.

Charlie now went to work on the problem of bad sound, coming up with the idea of chaining amps together to increase the power and finding speakers that would suit the human voice rather than an electric guitar. The result was possibly the world’s first 1,000-watt PA system, used at the 1967 National Jazz & Blues Festival, held in Windsor, to the west of London. It comprised WEM SL100 slave amps and a host of speaker cabinets with Goodmans dual-concentric-coned Axiom speakers. Artists on the bill, which included the debut of Fleetwood Mac, were astonished by the sound—as were the police, who prosecuted Watkins for sound pollution. Famously, the case was dismissed.

That first 1,000-watt system highlighted another problem with contemporary PA equipment—the lack of adequate mixers. Charlie’s answer was the five-channel Audiomaster, which soon became essential for touring bands, particularly when they realized you could chain two together and get the undreamed of luxury of ten channels! Check out the back cover of Pink Floyd’s 1969 album Ummagumma with the band’s WEM PA displayed as part of what by the standards of the day was a giant payload of gear.

Not only could singers not be heard by audiences prior to the development of WEM PA systems, but they could rarely hear themselves. Bands had begun to use columns as sidefills, but that had its limitations. Roger Chapman of Family stumbled on the answer. Frustrated by not being able to hear his own vocals, Roger had Charlie take the signal from an Audiomaster’s headphone output and feed it into its own amp and a speaker. "He always used to perform with a towel handy, because he used to sweat a lot," Charlie remembered. "So when I gave him the 1x12 monitor, he rolled up the towel, stuck it underneath, and hey presto! There it was—a wedge monitor for the first time. We found that made an amazing difference in the performance of a band."

Though PA was developing fast, column speakers still ruled. But that was also about to change. "Whatever you do with columns, you can’t project bass from them," Charlie told me. "So I made an exponential horn—a gigantic one coupled to a box with four Celestion speakers in it, facing each other into a three-inch channel with the horn bolted on." Charlie voiced it for his own ears, but when it was tested it was shown to have an almost perfectly flat frequency response. Still restless and inquisitive, Charlie experimented with parabolic dishes, but he failed to find speakers powerful enough to work with them.

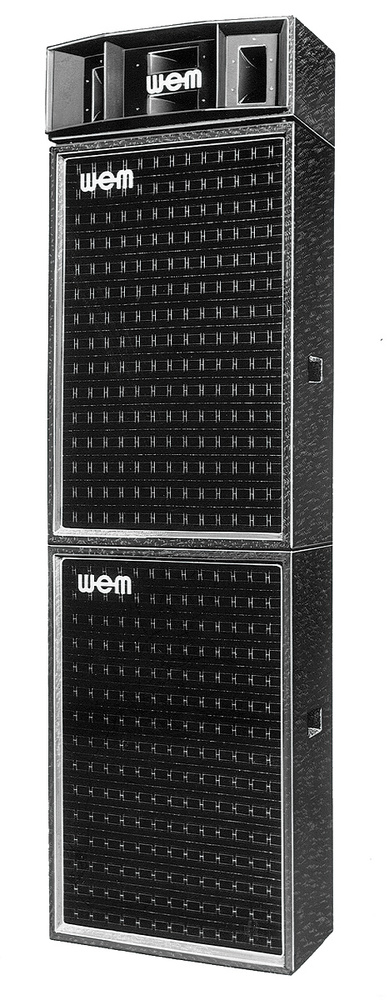

Perhaps the ultimate WEM system was the Festival Stack, which comprised a pair of 15-inch low-end speakers, six ten-inch speakers for mids and highs, and a Vitavox or Celestion horn for the top end. This was the WEM PA purchased by Janis Joplin, who may have been its first customer, though some believe it made its debut at the turning point of WEM’s PA history—the 1970 Isle of Wight Festival.

However, just as Altamont in the USA had shown the first hint of the darkness that followed the Flower Power era of the late ‘60s, the Isle of Wight festival—which turned out to be Jimi Hendrix’s last gig in Britain—saw the mood changing in the UK, too. Crowd violence was becoming more common, and problems with a high wind meant the sound was better heard several miles away than in front of the stage.

Charlie was told the sound level from his PA at a 1972 festival in Grangemouth, Scotland, was a constant 128dB and that this was supposed to be dangerous. "Then there was a bloke with a knife at a gig, and the audiences started to change. It was all starting to worry me," he recalled, speaking in 2010. "So I went to see a medical specialist and asked him if it was possible that I could be responsible for making people go deaf. He said, ‘Well, if it gets too loud, yes.’ I can hear as good as anybody today—and that’s after I’d sat in front of PAs for Thin Lizzy and Slade night after night. Well, someone had to be wrong. But, either way, it didn’t leave a very good taste in my mouth."

Coupled with these doubts, Charlie saw the technology advancing around him. By about 1973, he felt he didn’t have anything left he wanted to do. "Kelsey-Morris had come out with a version of the W-bin at about that time, and their system was better than the W-bin, and they were better than me. Although they were terribly heavy to carry, I could see what was going to happen. Here they were with a 500-watt box against a great big WEM system. It seemed like it was time for me to hang up my headphones. So I just stopped."

Today, Charlie’s legacy is maintained by his widow, June, who still runs Watkins Electric Music. A license to produce Watkins guitar amps and the Copicat echo unit is held by Amp-Fix in the UK, but WEM PA equipment hasn’t been made since Charlie closed his factory in 1974. Which isn’t to say it doesn’t appear now and again, but its attraction these days is purely nostalgic. If you’re tempted, though, do take care—it’s easy enough to stencil the name of a famous band on a speaker, a mixer, or an amp, so make sure you get verifiable provenance.