Editor's note: This post is part of a series of unpublished interviews from the personal research archive of noted guitar writer Tony Bacon. These interviews will be appearing on Reverb in the coming months.

Stay tuned for more interviews from Bacon's Archive coming soon. For previous installments, take a look at Tony's interviews with Tom Petty and Chet Atkins.

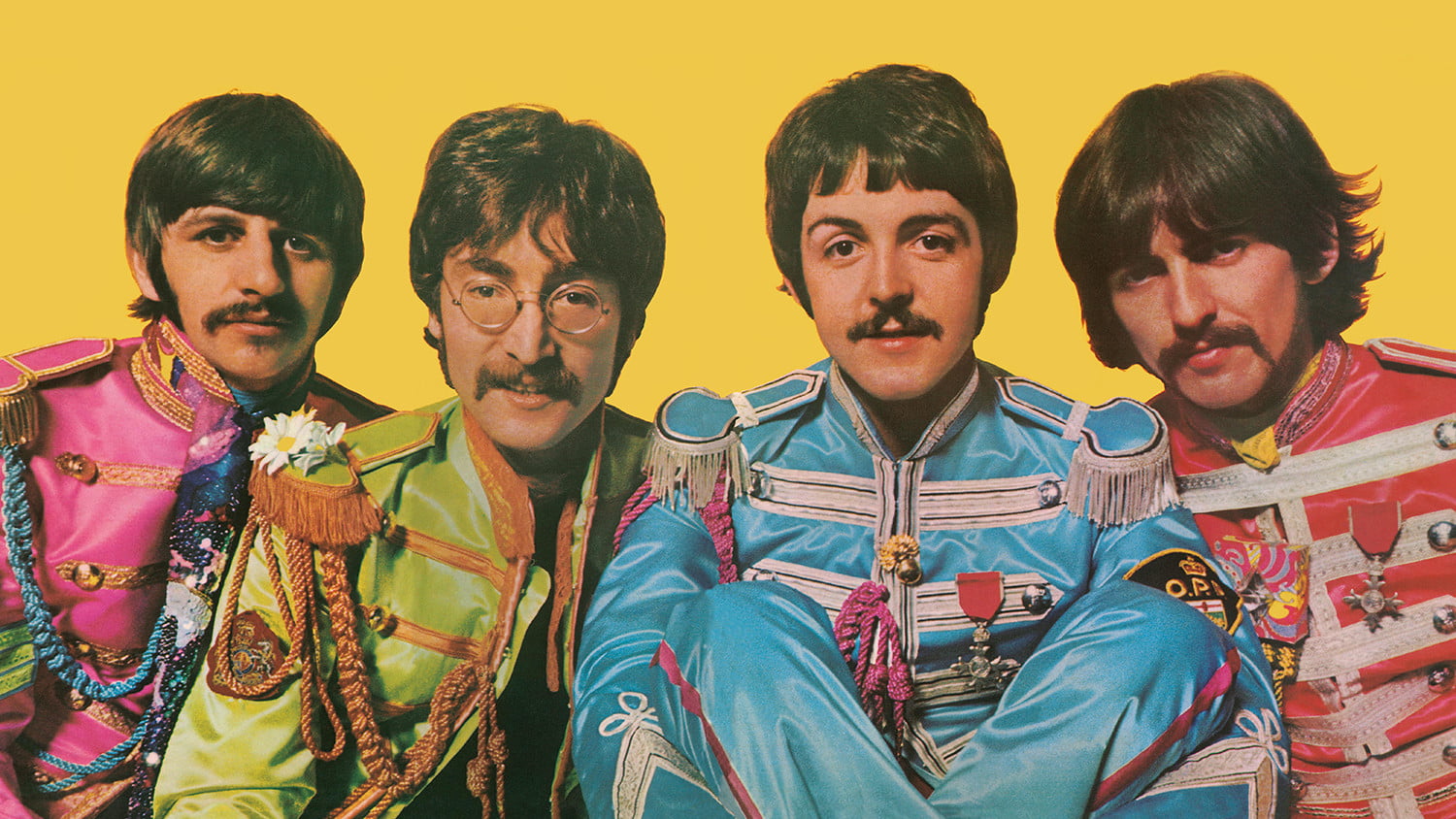

Fifty years ago, Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band was still riding high at number one on both the British and American charts. The Beatles recorded the album at EMI’s Abbey Road studios in north-west London from late November 1966 to early April ’67, releasing it in June ’67. Sgt. Pepper’s was not only a great commercial success, but it also popularized the idea of the concept album. Some even thought that it raised the pop music LP to the level of an art form.

Abbey Road had operated as a recording studio since it was purpose-built by EMI and opened in 1931. By 1967, there were three studios, with Studio Two as the prime Beatle recording location. Leading up from the live room (about 60' by 35' with a 30' ceiling) was a long wooden staircase to the control room perched behind a window, from where the producers and engineers could observe the musicians below. Sometimes The Beatles would use Studio One, Abbey Road’s biggest room (about 95' by 55' with a 40' ceiling) designed for classical and operatic recordings, and, rarely, the smaller Studio Three (about 40' by 30' with a 15' ceiling).

On the occasion of Sgt. Pepper’s first release on CD in 1987—a year that also marked the album’s 20th anniversary—I interviewed producer George Martin, engineer Geoff Emerick, and technical engineer Ken Townsend about the making of this most celebrated of Beatles records.

Geoff, can you tell me about the recording equipment you used at Abbey Road for Sgt. Pepper’s?

Geoff Emerick: There was no modified equipment: It was basically the standard EMI REDD desk, eight in and four out—and a couple of faders on those would accept an auxiliary input. We used Studer 4-track tape machines. Prior to that it was EMI’s own machines. [The Beatles did not have access to an 8-track recorder at Abbey Road until part way through recording the White Album the following year, 1968.]

GE: EMI were quite strict, like the BBC, on their technical specifications. Certainly the role of the engineer then was to work within those specifications—there were certain things you could do and certain things you couldn’t do. If something went into the red [on an input meter on the desk] you’d probably have to re-take something—and I know these days that sounds a bit silly. But with The Beatles we could be more flexible than with most people. I tried out various different mic techniques, for example, but we still had to be careful.

I remember we had a letter from EMI about the bass-drum mic'ing—they hated the idea of a mic being so close to an instrument that gave out such high-velocity air pressure, and they said it would probably destroy the mic capsule.

EMI liked you to wear suits and ties back then, too.

GE: Which we did [laughs], of course. All the way through this period.

The Beatles were somewhat more casually dressed, by ’67.

GE: Some bands did arrive in suits and ties, though. They really did!

And you had some fun with all kinds of musicians, Geoff … however they were dressed.

GE: Looking back on it, it was good training. I don’t know whether fun was the right word. EMI’s standards were extremely high, but being a staff engineer, yes, I could be working with one artist in the morning, another in the afternoon, and another in the evening—that was the way it worked. There were a few times when I might end up doing two or three artists at the same time.

How did the sessions work in those days, Geoff?

GE: The Beatles would normally start a session with a song idea. Normally we would finish a song, then go on to the next. But sometimes we would take something to a certain point, then, if we didn’t know what the solo was going to be, or there wasn’t a verse written, we’d leave it and move on to some other song.

The general procedure was that we’d start laying down the basic rhythm track—we’d start late in the afternoon, say 3 or 4 p.m., until 2 or 3 in the morning. That was unusual for EMI at the time—and so we’d be on our own then. We’d just do everything to get the master rhythm track, and keep doing takes until that one. Which probably meant going back on the reel of tape to take one again. The earlier stuff would have been take three or take four normally, but we’d go up to take 20 if we needed to.

On "Lovely Rita" they were stuck for a solo, and I suggested they do a piano solo. I can’t remember whether George or Paul played it—I think Paul. They were fed up putting guitars on for solos. I used to use a tape delay into the echo, recorded onto tape, and then delayed into the echo plate, but at the same time I was wobbling the tape and putting a high amount of wow and flutter on it, so the signal was going into the echo chamber and going up and down in pitch. That was done as an overdub.

But basically the procedure would normally be to record bass, and drums, and guitar or piano. We usually replaced the bass part afterwards as an overdub, because at least with four tracks we had the luxury of putting the bass on a separate track. All the drums would go on one track—there were no stereo drums. Guitar and piano on one track. Then we would go back and maybe drop in guitar and piano parts all on the one track, and maybe even mix the guitar, piano, and drums to one track, which would give us three tracks, including one for the bass replacement overdub. The vocals would go on the fourth track.

I remember recording the bass guitar—we always loved the bass-end of records. It always seemed to be the bass-end that was the backbone of the record, and to get the best bass sound ever was always a challenge. Every record we recorded, I remember, we were always going to get "the best bass sound." One of the theories we had was that instead of using a microphone to record the bass, we’d use a loudspeaker. A loudspeaker can push it out, so it must be able to take it in as well. Which we did, putting another loudspeaker in front of the bass stack. It sounded pretty good actually, though we didn’t pursue using it.

George, presumably one way to make more space on a 4-track was to mix several tracks down into a spare single track and start again? Which at Abbey Road you called a reduction.

George Martin: Yes, but we didn’t do that all that much. I don’t think we ever went beyond a dub of a dub. I tried to keep it to one generation loss. Sometimes we had to go to a second, but in the main I tried to keep it down.

And then on "A Day In The Life," to create enough space to record The Beatles and several orchestral passes, you used two 4-track recorders together. Geoff, what can you tell me about that?

GE: People might think that was done last, but the basics on "Day In The Life" were recorded quite early on, on one 4-track machine as usual. The orchestra part was done some weeks later, on a second 4-track.

George, didn’t you have trouble running the two 4-track tape recorders in sync?

GM: Well, we didn’t have any sync facilities in those days—they just didn’t exist—so we had to do it purely and simply by guesswork. So what we did was to record the orchestra on a separate 4-track, and we did lace them back in again afterwards. That’s why you can hear a little bit of bad ensemble… you can hear several versions of the orchestras slightly different from each other.

Presumably that was manually spun back into the 4-track.

GM: It was done manually—or as Peter Sellers would say, "In other words, once a year." [George produced some comedy records with Sellers solo and in The Goons.]

There was no electronic link?

GM: No, that was the only way you could do it in those days. We didn’t have any way of syncing up.

Is that your recollection, Geoff?

GE: To link the two Studer recorders, yes. It was trial and error. We couldn’t sync them like we sync them today [1987]. We recorded the orchestra on a second 4-track machine—basically, it was spun in. Ken was the maintenance manager at Abbey Road then, and he always knew the right way to do these things.

Is that right, Ken?

Ken Townsend: At the time I was technical engineer at Abbey Road, and I did this at George Martin’s request. George put me the problem: we haven’t got an 8-track, so can you find me some way of linking machines together? The Beatles were on one 4-track, and I think we recorded three or four orchestral tracks onto the second 4-track machine. I put a 50Hz tone on the first machine, the one with the backing, and made that one drive the second machine, the one with the orchestra, through the capstan motor of the second machine.

Then when George was mixing it, he had a job to start the two machines together in sync. It was the first time those machines had been linked together, actually. We recorded it in number One studio, but we mixed it in Three. The biggest problem was that when we went to mix in Three, we used two entirely different machines. We used exactly the same system, but the problem was starting them manually.

You can put a marker on two machines, and one starts the other one, but two different machines won’t start instantaneously. It’s not like Q-lock now [1987]. So those two machines were electronically linked, but they had to be manually started, and we had to make sure they started at the right time. Once they locked up in sync, it was fine. We only used that on "Day In The Life."

GE: The idea on the orchestral part on that track, I believe, was to start on a certain note and end up on another note so many bars later. So to get the actual beats of the bars, [tech] Mal Evans actually counted out one, two, three, and so on for the bar numbers, and when it came to the last bar he set an alarm clock off—although it’s not supposed to be an integral part of the track, but we were picking it up over the loudspeakers.

On "Good Morning Good Morning" the brass has a wonderfully punchy, bright sound. How did you get that, George?

GM: I know we endeavored to get a very hard sound and that Geoff took a great deal of trouble over that. It was Sounds Incorporated’s brass, and they blew very hard anyway. Obviously it was very heavily limited. I suspect in fact it was Geoff’s normally very good use of the Fairchild. I do agree with you, it was a very punchy sound, but a lot of that was to do with the band. They did give us an awful lot of bite on that, that was unusual for the time.

GE: The Fairchild limiters and compressors do sound incredible. You can put a guitar or vocal through them without it actually limiting or compressing and it sounds like it’s four feet closer!

The [1987] CD booklet notes say that Abbey Road’s Studio One was used for "Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band (Reprise)," although Studio Two was used for most of Pepper. Do you recall that, George?

GM: Most of Sgt. Pepper’s was done in Two, yes. "Day In The Life" was done in One, and "When I’m Sixty-Four" was done in One—which may strike you as being a bit funny for just three clarinets, but it was. I don’t know why "Reprise" was done in One rather than Two. It’s quite possible we couldn’t get into Two at the time. I know "Reprise" was done very much towards the end, and The Beatles and I were continually flinging people out of the studios, because we wanted to muscle in on them, putting pressure on them, saying, Look, we’ve got to finish this, do you mind moving to another studio?

Maybe on this occasion we couldn’t get into a studio at all except for number One—that’s the most likely explanation. Geoff and I probably said: Let’s do it in One, we can probably cope with it. And in fact I don’t think it’s a bad thing. I think it helps the atmosphere of the performance of "Reprise," the ambience. But I don’t think we designed that.

GE: The main "Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band," the one that opens the released album, was done in Two, but the "Reprise" of it was recorded in the large studio, number One. And yes, I think that was because someone else was using Two, and it was one of the rare instances when they couldn’t get into that studio. Did it make a difference? Well, I liked the "Reprise." I thought it was harder, because number One studio is enormous, and the drums were flying around the room everywhere. But the sound on it is really good—it’s biting.

Also, the CD notes say that "Fixing A Hole" was started at Regent studio, a small independent studio in central London. George, I wasn’t aware that The Beatles did much outside Abbey Road.

GM: Well, they didn’t. I’m afraid the boys didn’t plan very much, and when they wanted to come into a studio they never said to me, Keep the next two weeks free because we’re sure we’re going to be needing a studio. They would ring me up at 10 in the morning and say, We want to record tonight at seven o’clock… OK? And I had to find a damn studio.

GE: That’s right. From what I can remember George and I were doing another album—I think, we had to do something—and The Beatles wanted to carry on working. So the only thing that could be done was for them to go and work in another studio, which they did. George and I were doing Cilla Black, or something.

Who would have been in charge?

GE: Well, Paul would probably keep it all together. If that situation arose, Paul would take charge.

George, can you recall any other times during Pepper that you weren’t available?

GM: Yes. Dave Harries [another Abbey Road engineer] reminded me that neither Geoff nor I was present at the beginning of "Strawberry Fields Forever." That track was the beginning of the Pepper album, and "Penny Lane" too. They sound like it, don’t they? [Both recordings were started in late 1966, released as a double-A-side single in February 1967, and did not appear on Pepper.] Anyway, it was one of those occasions when The Beatles said, Look, we want to come in at eight o’clock, OK?

Both Geoff and I were going to a premiere, I think of a Cliff Richard show, at 7 o’clock. So we said, Can’t make it today, John. He said, Well, we’ll come and start off and you join us when you can. We probably turned up about 10:30, 11. The only person available was poor old Dave Harries, who was the backroom boy, the maintenance engineer, and he had to cope with setting up the mics and giving The Beatles what support he could by himself, with another tape-op, and they did that until we turned up.

Did you record any other things that weren’t used for the album?

GM: We recorded "Only A Northern Song," that was done during the Pepper period, but for obvious reasons, we didn’t [laughs] put it in Pepper. It was one of those things that got shoved aside until the boys eventually said oh, that’ll do for Yellow Submarine. They tended to look at Yellow Submarine as rather like a poor relation. They would give it their least worthy titles.

On "Getting Better" there’s a large number of engineers credited [on the 1987 CD release]: Malcolm Addey, Ken Townsend, Geoff Emerick, Peter Vince, Graham Kirkby, Richard Lush, and Keith Slaughter. Why was that, George?

GM: I’m surprised at that. I can’t think what Ken is doing there.

KT: I’m credited on that because Malcolm Addey used to go home at midnight. So somebody took over—I took over to carry on to 3 or 4 in the morning on two or three occasions. The number of engineers credited is because it was done over several sessions on several nights. Sometimes if the regular guy is away a bit of a stopgap goes on. But Malcolm Addey, at midnight he’d say, Right, I’m going home now. And so when I was technical engineer, once or twice I took over from him.

At that time Pepper was recorded—late ’66 into the first few months of ’67—were you still an employee of EMI, George?

GM: I’d left. I left EMI in September 1965, so I’d been away for a year and a bit. During that year I’d been away, I’d been working like an idiot anyway. We’d just started AIR. [Associated Independent Recording was the company George set up with another ex-EMI producer, John Burgess, in 1965.] AIR had a very shaky beginning, four producers and three girls—we didn’t have any money to start with at all. We had offices at Baker Street, almost opposite where the Apple people opened later on. We were on the top floor, pokey, above a bank. We hadn’t started building the studio [at Oxford Circus] because we had no money. I started building a studio in 1968, a year or more after Pepper.

What was your relationship like with EMI when you started Pepper?

GM: As far as using Abbey Road was concerned, my relationship with EMI was completely unchanged. I’d grown up there and lived my life there, all my mates were there, and I was there. Even though I wasn’t on a payroll.

Did it change your attitude to things?

GM: Not at all. Not to working in the studios. As far as the main company was concerned, I was a bit of a maverick who they were glad to get rid of.

Well, their loss.

GM: They tried to persuade me very much to stay. It was tough. AIR really was hard at the start, with no money. It was meeting bills, hoping the money would come in. The other boys, [producers] Peter Sullivan [from Decca] and Ron Richards [from EMI], were making records, and we were all firing money back into the company. We didn’t earn anything much at all in those days. But it was a good atmosphere and I had no problems with relationships within the studio, because they were all my mates.

Did you take longer back then to mix the mono album compared to the stereo?

GM: Generally the format was that we and The Beatles would mix the mono one together, and Geoff and I would mix the stereo ourselves after the boys had gone home. By the time Pepper came along the boys were much more interested in stereo, and in fact they got really into it, but not as much as they did later.

GE: I’m sure we did rough mixes as we went along. But all the mixing was done at the end, and I remember it took three weeks to mix Sgt. Pepper’s in the mono version, which was the intended version. Stereo in England wasn’t—

GM: That’s right, absolutely: stereo wasn’t important in the '60s, it really wasn’t. It’s difficult for people these days to understand the technology in those days and how primitive life really was. And the kind of way that people listened to their records at home, too—the machines they had were pretty awful.

GE: Anyway, The Beatles went on holiday and George and I mixed the stereo version in three days, I think. So the [vinyl] record to have is the mono version.

The [1987] CD is only available in stereo.

GE: Oh yeah, which is fine. It sounds good, actually. It’s tricky to get two electric guitars to sound different out of one loudspeaker—it’s much easier to have one guitar in one speaker and one in the other. When they’re coming out of the same speaker you’ve got to get really different tones around the guitars, you’ve got to get the separation and distinctiveness on the thing. It takes forever to try to mix that.

Grammy for Sgt. Pepper.

So the mono one is the one to have. The mono version is the way The Beatles accepted the album, because they were present, and it’s got finer brush strokes, which probably the stereo version hasn’t got—because of our old problem of only having four tracks, having all the echoes on one track, and things like that.

Is there such a thing as a favorite track? For you as a producer, George?

GM: Oh, I’m very happy about my involvement in "Being For The Benefit Of Mr. Kite!" because I think I really contributed quite a lot on that one. I do like that track very much. I like "She’s Leaving Home" very much, a super track… even though [laughs] I didn’t do the score. [The strings arrangement was written by Mike Leander.] And of course I’m very proud of "A Day In The Life." I’m still amazed that the BBC banned it. They banned it a month before it came out. Somebody had heard it and said, We’re not going to play this, it’s terrible. Difficult to believe, isn’t it?

GE: "She’s Leaving Home" was another instance where we were doing Cilla Black, I think. Paul didn’t want to wait a day for George to get together with him—I don’t know why. I think Mike Leander went round to Paul’s house—Paul’s normally got the ideas in his head and he plays it on piano. Based on Paul’s idea, normally. It’s a nice arrangement.

It was harder to get session musicians then—you could find yourself ending up with a pretty duff orchestra. You always knew when people are playing good and playing bad. Back then at EMI, most days you’d probably have an orchestra in number One, in Three, and in Two. Now [1987] you’ll find one orchestra a month.

"Kite" started with drums, bass, harmonium, and John’s guide vocal, but then John asked you for a "circus feel," George, and you found some archive discs of fairground organs and so on, which you transferred to tape. Geoff, I believe you were then asked to cut up the tapes, throw them in the air to mix them up, and splice them back together more or less randomly … for the swirling sound we hear on the record.

GE: Well, the tapes only accounted for a little bit of it. For that fairground sound on "Kite" we had one of the mammoth overdubs, again because we were only on a single 4-track, so we had only one track left to do all the overdubs. On that particular overdub track for the fairground calliope noises, I think George Martin was playing harmonium, someone was playing glockenspiel, someone was playing another piano, someone was spinning the tape fast, slowing it down—but we had to do all this in one fell swoop.

I remember George ended up sort of spreadeagled, collapsed on the floor, because he’d been pumping the harmonium for about four hours. We finally got the take about 2 in the morning, having started the previous afternoon. You could drop-in then, but you couldn’t do fast drop-ins as you can now.

Are there other particular tracks that stand out for you, Geoff? How does it rate of the albums you engineered with The Beatles?

GE: It’s still my favorite. Good memories, as well. I like "Within You Without You," that’s one of my favorites. It was the first time we’d applied sort of pop techniques to recording tablas. No one had ever mic'd these instruments closely before. Same with the sitar and the tamboura, things like that.

There was nothing in the EMI handbook about that?

GE: No [laughs]. I remember after recording "Within You Without You," about a month later we were working at Abbey Road recording an album and the engineer was recording a sitar with mics about 25 feet away, and they couldn’t understand why they couldn’t hear it properly. For Pepper, we had the mics basically inside the sitar. It was good fun, actually. Working through Pepper we were always looking for something different. Really getting into the instruments.

If you listen as you walk around an instrument, or put your ear close to it, it’s amazing what you do hear. If you put your ear near to the edge of a cymbal, the note is so low it’s incredible, you’d never believe a cymbal could issue that particular note. You’re used to a high crash from it. So we looked for all sorts of things like that.

George, were there any working titles for Sgt. Pepper as an album?

GM: No—not that I can remember, anyway. We never had working titles for albums. We had working titles for songs. If a song came along that didn’t have a title, we’d say, Let’s call it, say, "Scrambled Eggs" [the working title for "Yesterday"]. Never for an album. And the title wasn’t arrived at until the album was finished. People would say what shall we call it? We generally ended up with a good title at the end of everything. In the case of Pepper it became that almost before the end, because of the nature of it, the way the thing knitted together.

What was the process for transferring the Sgt. Pepper analogue master tapes to CD [in 1987]?

GM: I haven’t done anything on the CDs. All I’ve done is approve, really. I’ve listened to the tapes in their original form and monitored that they were being transferred well and that the EQ characteristics were fitting for the CD. That’s really all. I deliberately didn’t want to start messing about with mixing. But we did re-introduce the old giggle at the end, the run-out groove, and the 15 kilohertz sound for dogs.

Obviously on a CD you don’t have a run-out groove, so I thought let’s do it as it would have been on an old record. So the couple of seconds or whatever it was that was the completion of the circle of the run-out groove, you hear that, then you hear it start again. You hear it going on and on for about nine or ten times, and it eventually fades out.

Which is probably as much as anyone would stand normally.

GM: Yes [laughs], and you can always program your CD player not to play it anyway.

I presume you did those fun things for the run-out groove of the original vinyl at the end of all the sessions?

GM: Yes, it was just after we put all the thing together, and we were all feeling very buoyant and happy and high. I think it was John who suggested we had the sound for dogs… because the animals never get any good sounds for themselves. He knew that dogs could hear higher than human beings, so we thought 15kHz was about right. Because some people would be able to hear it, if they have good hearing, so we shoved that on. The noise at the end, on the run-out groove, it was just a giggle. Why don’t we put something for those with non-automatic players where the needle doesn’t pick up when it gets there? Most people would never have got to that point. It was just an idea that if anyone did get there, they’d get a shock. A trivial joke, really.

GE: We’d basically finished the album and they were going on holiday on the Saturday or Sunday, and because the adrenalin was off and the album was finished, the idea was to put a high-frequency noise for dogs at the end. And the backwards voices—they went down to the studio and spoke anything that came into their heads.

Ken, in the [1987] CD notes the cost of making the Sgt. Pepper’s album was estimated at £25,000. Any idea how that was worked out?

KT: I’ve got a feeling that in those days recording cost about £25 an hour for 4-track. I suppose they then added the cost of the musicians, of which for example there were quite a few on "A Day In The Life."

Who cut the master for the vinyl album?

GE: At Abbey Road the cutting was done by a man called Harry Moss. I remember on the actual tape box on the master I put “transfer flat,” which meant that the cutting engineer should not alter any equalization or compress anything. Because in those days you didn’t have the sophisticated cutting lathes that you have now, and you had to be very careful what you were doing to get it on to vinyl. But we didn’t want it to be interfered with in any way. And I was reprimanded for not putting the word “please” on that message on the box.

Did you go along to the cut, then?

Yes. I had special permission.

George, how do you look back on Pepper, hearing it again now [1987]?

GM: Well, I’ve heard it recently because of the CD release. I hadn’t listened to it much before then. I found it fascinating going back to it and listening to it, particularly opening up the tracks and listening to some of the 4-tracks, hearing the outtakes and things. That was fascinating. It is fascinating listening back to something you did 20 years ago. I do think it stands up very well, I’m very pleased with it.

There are one or two irritations that I think if I had my time over again I’d do it differently. I would put a much longer gap between the end of "She’s Leaving Home" and "Being For The Benefit Of Mr. Kite!" It’s such a poignant song, and "Kite" rather jars on you. I thought it was hip at the time, so there we are. Another thing when listening on CD is I hear the hiss of the records that were used to dub in the sound effects on "Good Morning." They were taken off [vinyl] disc. You didn’t notice it too much on the vinyl of Pepper, but my god you notice it on the CD! Sorry about that, folks.

About the Author: Tony Bacon writes about musical instruments, musicians, and music. He is a co-founder of Backbeat UK and Jawbone Press. His books include The Ultimate Guitar Book and London Live, and he edited the various editions of Beatles Gear. His latest book is Electric Guitars: Design And Invention (Backbeat). Tony lives in Bristol, England. More info at tonybacon.co.uk.